|

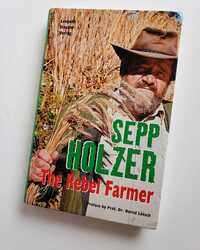

Back in 2006, the high fuel prices during the Iraq War, in conjunction with the Ethanol Mandate, had resulted in skyrocketing feed prices. Gas was over $5 a gallon. Diesel was even more. The duck feed I was buying had just about tripled in price. The bags of wheat, for example that I used to buy for sprouting grains for my ducks feed mix, went from $16 a bag to $46. I gradually doubled the price of my duck eggs, in order to cover the increased feed costs, but as a result I lost half my customers. Then the economy crashed and I lost 95% of the rest of them. I knew of other small farmers in my area in a same situation with skyrocketing feed prices with their organic chicken egg production. They simply decided to cut their losses, and sold all their layers to be butchered for pet food. I could not do that to my lovely Welsh Harlequin ducks, so I forged on at a loss. I ended up shoveling hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of expired duck eggs into my wood shavings compost pile. All that work, all that expense, wasted. I decided that in order to not be at the mercy of rising fuel prices, and its effect on feed prices in the future, I should jump start my life-long dream of a “One Straw Revolution” grain field, and grow some of my own grains.  My one acre grain field. My one acre grain field. In order to accelerate the project, I decided to break my own rule of no-till on my farm, and to have just a one acre area at the bottom of my hill tilled up, so that I could start growing some grains right away. I asked my neighboring dairy farmer, that I had bought my 20 acres from, if he could plow up an acre for me. He said that he didn’t have the equipment to do a good job for my purposes, and he highly recommended a guy that did plowing for intensive vegetable operations. I hired him, and he came over and turned over the sod, and then roto-tilled the field smooth for me. I broadcast seeded Kamut onto the soft, evenly churned up Loess/clay topsoil, on an eighth of the acre, and the rest I seeded heavily with buckwheat. My idea was that if too many weeds came up, I would have it all plowed under again, and reseed with another crop of buckwheat. When the rains came, it all germinated nicely and I was very excited. Then an understory of mustard weeds came up and bloomed, and I had a solid acre of beautiful yellow mustard flowers. I could still see the grain rising above it though, so I was not worried. Then the next wave of weeds that germinated was ragweed and foxtail. It also rained and rained that summer, and my Loess/clay field was too wet to plow. The new weeds quickly overtook the grains. The one acre grain field turned into a field of 3 foot high ragweed, mixed with foxtail grass of the same height, and everything was intertwined with red clover. You could still see the grains, if you looked down in between the tall weeds, but there was no way I was going to be able to harvest it. Unfortunately the torrential rains persisted, and my little field became as wet as a rice paddy. There was no way to plow the weeds under either. I really did not want all that ragweed and foxtail to go to seed, and to have even more weeds to deal with in the future, so I decided to mow it all down with my scythe. Scything down an acre of 3 foot high ragweed was a lot of extra work that I had not planned on. I looked at the positive side of it, and regarded it as a giant, chop-and-drop, soil-building, weed-prevention exercise. Having the field plowed had brought up a lot of small glacial-till rocks, so I had to hold my scythe blade about 3 inches above the ground in order not to be constantly cracking the peened edge on the stones. This was more easily done by simply lowering my grips a couple of notches. I also had a wildwood snath that was a little too short for me on the bottom, that turned out to be just right for mowing above the ground a few inches. Parts of the field were so wet at one time, the water level was above my shoes, so I had to mow a couple short strokes and then gather up the cut stems into a pile with my blade, so that I could stand on it, and then mow another little pile and so on, until I got to an area with less standing water. I also have a severe ragweed allergy, but I’ll spare you those details. I did manage to mow it all down, before the ragweed and foxtail went to seed, and I spread out the cut stems evenly over the field, to compost in place. When it had dried out, I broadcast cereal rye seed over it. I find that when hay or straw mulch is dry at the surface, seeds fall down through the cracks of the stems down to the humus layer. The rye seemed to come up quite nicely. Either that, or the original pasture grasses that I had plowed under, resurfaced. Most likely a mix of both. By fall, my geese had a lovely fresh pasture to graze, and they enjoyed it immensely. They would waddle out into the pasture to graze, and when they were full, they would flap-and-fly back to the goose barn area. By spring, it looked like I either had a one acre field of rye or a mix of grass and rye. Then the mustard came back, and it turned the field into a beautiful, solid one acre yellow rectangle again. I wasn’t too worried. But then the mustard was followed by fleabane. At first, I was not worried by fleabane. It usually seemed like an innocuous weed, but to my surprise it grew to be 4 feet tall! And thick! I had a solid one acre field of incredibly dense, 4 feet tall fleabane. I had never seen fleabane so big, nor so much of it. My farmer friends were amazed as well. They had never seen anything like it either. It was like a super weed. (Note: I am 6'5" tall and the scythe customer in the video below is taller than me.) There was so much of it to mow down that my progress was very slow. Unfortunately, I did not get all the fleabane mowed down before it went to seed, because I was busy with many other projects. The stalks became so mature and tough, it was easier to mow with my light bush blade. I had a couple of WWOOFers working with me that summer, and one of them valiantly pledged to finish off mowing down all the fleabane stalks. She got up early every morning and scythed away at the field before it became too hot. She almost succeeded before she had to leave. If she could have stayed a few more days she would have finished it all. She did say that scything in the morning was a great way to start her day. It really made her feel good and got her revved up for the day. A sentiment which I share, and I have also heard that feedback from many others that I have sold scythes to. I managed to finish scything the rest of the fleabane stalks down by the end of summer. By the time I got to the last part of the field, the fully mature and dry stalks were so big and rigid that it left a high and jumbled mess laying in the field. So I forked up all the cut stems into my garden cart and hauled load after load over to the new windrow garden beds I had been establishing. I got the fleabane stalks aligned, pressed together, and stomped down as the final layer of mulch for the year. Grasses and clover dominated the "grain" field that fall, and once again my geese had a lovely pasture to graze. In reflecting on the futility of all the extra work and expense in my attempt to simply grow some of my own grains, I felt like Sisyphus perpetually rolling his boulder up the hill. I compared that to in contrast to the ease and reliability with which I could harvest reed canary grass for straw every November, from a different part of the same field less than 100 yards away. I never had to worry about it being taken over by weeds. It made me wish for a grain that could establish itself as a naturally dominant monoculture like the reed canary grass.  Sepp Holzer's book cover showing him holding a handful of his Siberian rye. Sepp Holzer's book cover showing him holding a handful of his Siberian rye. I had read about a Siberian rye in Sepp Holzer’s books “The Rebel Farmer”and “Sepp Holzer’s Permaculture”. He says that in 1957, he saw an ad in an Austrian hunting magazine for an ancient Siberian rye that was a great grazing plant for wild game. It was very expensive, so he only ordered 1 kilogram of it and grew it out for seed. He was very happy with it, and has been selecting and breeding it ever since. According to the book, it makes a great pioneer plant for newly disturbed areas. Grazing animals love it. Once established, it can be grazed, or mown for several years, before allowing it to head out and set seed. Setting in back by grazing or mowing, makes it regrow bigger and increases the final yield. The straw is 2 to 2.5 meters high and is strong. It is useful for animal bedding, crafts, and for straw mattresses. The grain makes wonderful bread. Once it sets seed, its lifecycle is done and you can plant a different crop. What if I had seeded my newly plowed field with this Siberian rye, instead of buckwheat? Then when the ragweed and foxtail had germinated and outgrew the Siberian rye, I could have mowed the field with my scythe to set back the weeds as before, but the base of the rye would still be alive and it would grow back, getting bigger and stronger. Then when the rye came up in the spring the next year but the fleabane took over, I could have mowed down the fleabane, and still had the rye growing. In fact, I probably could have mowed the field when the mustard was in bloom, and set back all of the above weeds at a much earlier, more succulent stage, when the scything would have been much quicker and easier. I found a source for Sepp Holzer’s rye seed. 100g of seed cost about $50. I bought 100g of seed and started growing it out in my garden.

1 Comment

Leon

10/21/2020 05:29:50 pm

This is a great story Botan and even though you may not have initially succeeded with what you set out to do, you still did a lot of good soil building and got a lot of mulch out of it. You’ve inspired me in a huge way, especially your windrow gardening which I’ve adapted to my tree seedlings in our young food forest.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Botan AndersonArchives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed